Definition of a cairn: a small quantity of stones heaped together that usually marks a place

We leave the house equipped with sandwiches and cameras. I even have my sketchbook, although not sure I’ll get to use it. Through the gate and turn left up Robert’s useful recently-made track that winds up the hill. Sunshine and blue sky, a lark sings somewhere high to my left. The first cairn and a whole lot more lie somewhere ahead.

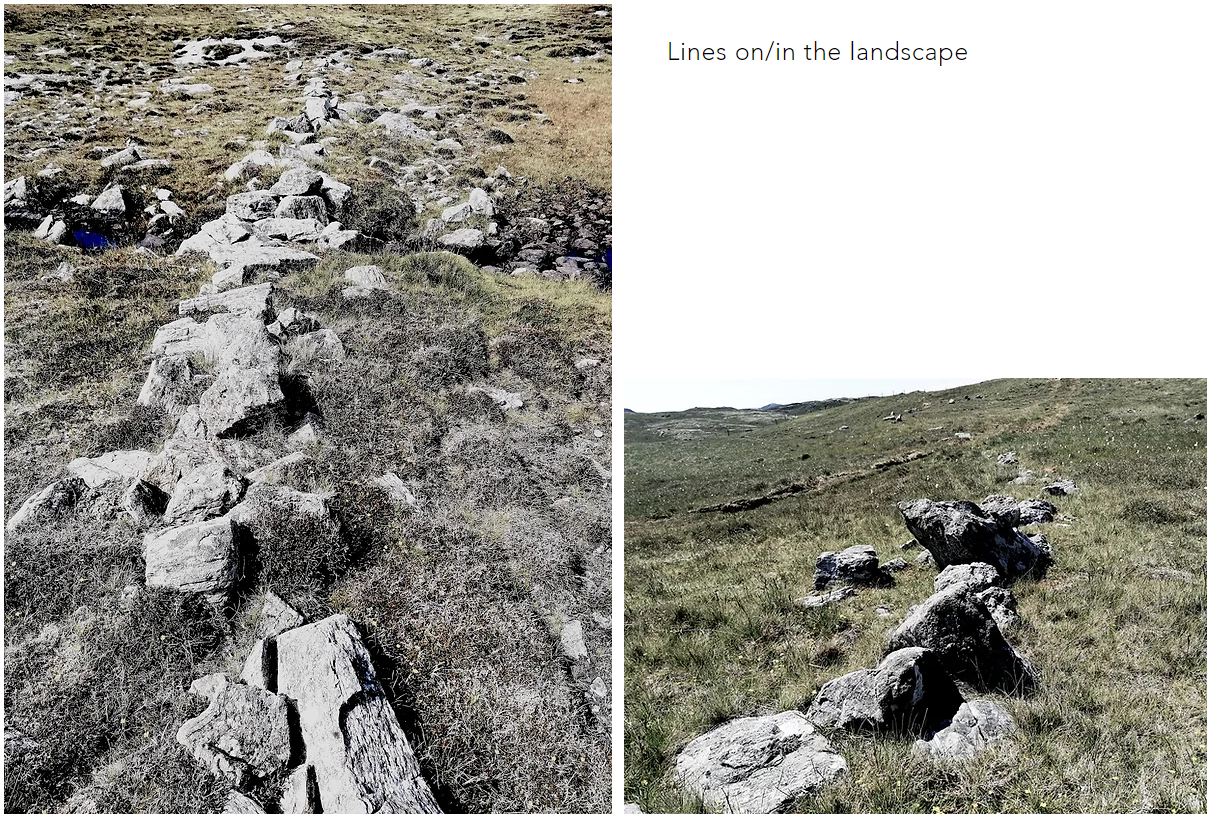

Too soon I’m distracted by a row of old stones winding across the hillside; once they marked a field boundary; I wonder whose hands rolled them into place and how long ago?

Curlew calling.

The remains of an old stone structure – a ‘plantie crub’ – a circular enclosure where the ubiquitous Shetland kale was once grown, the walls protecting from the strong winds and rabbits, as well as creating a micro-climate. Who built it? When it was last used? Too many questions so early on my walk is not good. These hills were once farmed extensively – as ‘scattald’ local people could graze their animals, and grow their cabbages. The land is slowly recovering; interesting plant returning

Circles on the land

We follow the line of Robert’s fence up the hill. The ground is unusually dry, sounds crisp underfoot; the moss makes it soft and springy. I’ve roamed across this area many times and am very familiar with it, but I'm defamiliarising myself with it by walking in a different way by choosing to use the cairns to lead me. Creating new lines. It’s always different anyway, always something new to notice, the light alters how it looks. Lochs to gaze into, interesting plants and creatures to find hidden in the grass. I find a tiny vivid blue flower lying almost unnoticed at my feet.

Sheep and lambs cease grazing, watch warily while we approach, scatter as we pass.

The ground is covered in yellow flowers; even tinier white ones in between.

Hundreds of old man’s beards shiver on thin stems in the breeze.

As I climb two black-backed gulls circle constantly overhead, calling and harrying me, swooping down close enough that I hear the sound of their wings as they pass. I have entered their space and they are making sure I know. Undeterred I make my way between two lochs.

There’s another distracting row of old boundary stones marking a line between the two lochs; I pause to wonder, then crouching down to peer into the grass. Where the ground is damp, groups of small sundews glow crimson, their sticky tendrils glistening in the sun, awaiting a hapless fly. They are amazing beautiful constructions.

Just read that the ‘dew’ of the Drosera Rotundifolia (round-leaved sundews) once formed the basis of anti-ageing potions - people believed it was a source of youth and virility. The plant was also used as a love charm because of its power to lure and trap insects.... hmm.

Onwards; rocks rise in front of me; small brown wheatears hop about between them making a kind of ‘tutting’ noise, ending on a high pitch cry. They are seemingly uninterested in my presence. Above lies my quarry.

A small cairn lying above Catherine water. It looks as if it’s wrapping around something, hugging the stones inside. I walk the circumference. From up here lochs and land stretch out around us, and, just visible on the horizon, there’s the next cairn.

The wind’s getting up, a pale haze of clouds starting to form. Somewhere below me on the loch there’s a family of red-throated divers (called rain geese here) on the loch. I can hear their mournful, slightly eerie, call floating up on the air. Good to know they’re back again.

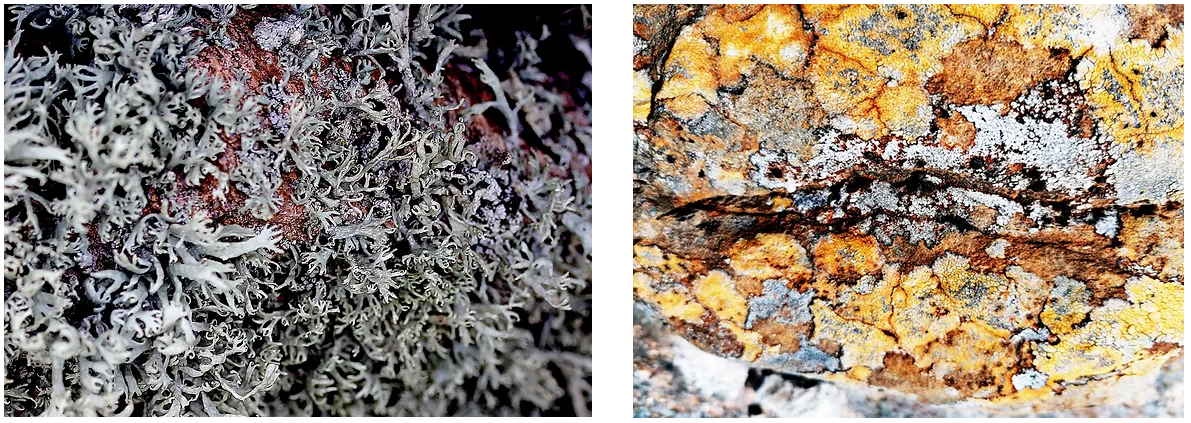

All these cairns are old and worn, warm and rough to touch, their surfaces covered in lichen. I have no idea how long they’ve been here, or who built them. The rocks here and on which we walk on are ancient - second oldest rock in the world - Basement Gneiss (Grenville), formed between 2900 and 2500 million years ago. A pause for thought, and the phrase that was mentioned earlier today in the ‘walking the land’ zoom meeting about there being 'a thousand worlds in this one world of grass'. (John Madson’s 'Where the sky begins’) comes back into my head.

I walk around each cairn, doing a bit of maintenance replacing fallen stones; some of the rocks have pink granite fused with the dark gneiss; thick rivulets of white quartz run through others.

I’ve been reading a book written by a geologist travelling in Greenland. I don’t understand a lot of the terminology he uses, but it would be useful to have him beside us to talk about these rocks, to know where they’ve been, what they’ve seen, what changes they’ve experienced as they were formed.

We spy the next cairn ahead of us - a handy perch for a seagull to cast its sharp eyes across the land.

A large cairn, and from the top we're in sight of sea, but not that close. The black-back gulls are feeling displaced by me, calling their annoyance as they circle.

The cairn overlooks sea. More hopping-about chattering wheatears. Lunch stop and the sun’s out. I remember to circumnavigate the cairn, do a few repairs, and take a 360degree panorama before we leave for the next one, walking parallel with the sea (on our left) and hills to the right and ahead.

A small fledgling cairn... which looks dramatic when I photograph it from the other side - looking into the sun.

There is so much space to breath up here. I could spend hours just gazing out across the sea, watching seabirds wheeling and clouds passing, colours changing, listening to the wind and the birds calling.

Time for a brief snooze lying on sun-warmed rocks, before continuing our tour of the local cairns.

Ahead of us on the horizon sit three cairns in a row, each on its own hilltop.

We make our way down, crossing rough grass and heather, rounding rock faces, skirting boggy bits, jumping over small streams. Then climb upwards again over the rocks and make for the cairn nearest the sea.

Being so close to each other these must have been used by fishermen as meids to navigate their way out to the fishing grounds and back, lining each up with the other to form a tringle. Looking out to sea we can see across to Papa Stour one way, and all the way to Stenness the other, and then back inland. Sky clouding over, sun still glowing on the red granite rocks of Muckle Roe across the bay.

As we arrive below the cairn a Great Skua (Bonxie) circles overhead watching, swooping close, then landing on the hillside, then taking to the sky again. We suddenly realise that it has a young one – still featherless – well hidden in the grass, and we make a detour away from it before climbing to the top of the cairn. Standing surveying the landscape, we see the Bonxie is hunting; below us is a goose with a brood wandering about in the grass. The Bonxie makes a sudden dive and grabs at one of the small goslings – they all scatter in panic and the mother rushes to defend her children. Another dive; surely it’s got one? The problem (or perhaps the saving grace) is that Bonxies don’t have claws and can’t carry off their prey (their feet are webbed), so it comes away with nothing, but it’s difficult to see what’s going on. There’s a third fast dive down to the ground, and it looks as if there is impact, but the mother goose has got there and is defending her chicks. A black-back gull arrives and decides to intervene and attacks the bonxie, which takes to the air, flying off to sit on the far (our next destination) cairn. We have just witnessed nature in action.

Time to move on. As I climb down I find a tiny pale blue flower in the grass - it looks like a star. Again I have no idea what it is and can't find it in our wild flower book. Going to have to ask on the Shetland wild flower facebook page

We usurp the Bonxie, who flies off before we get there to occupy the one we have just left. I forget to do the 360° photograph.

At each cairn I've been photographing the lichen growing on the rocks – pale greens, orange, browns, white, even black - I’m sure there are names for all of them - call for another expert! Some spread across the rocks like a coloured patchwork quilt.

That’s enough cairn spotting and visiting for one day. There are more but they can wait for another day. Time to go home. Sea loch on our left, we make our way up and down and up (again) the hills. Oyster catchers sound a warning overhead.

On the way back we cross another line of old boundary stones. The landscape up here is littered with them.

Just before we get back to the house we arrive at a last mound of stones and argue about whether it’s really a cairn or just a heap of rocks that was once a wall - depends on the angle you look at it and there is a good view out across the voe from here.. so maybe... But we can also see our home and we are tired and it’s definitely time for dinner.

So do these cairn become markers on the land and create liminal spaces that we enter and walk as we travel between them? It makes for a different way of mapping and walking and observing the landscape. Of walking a line between. From some places we can see many of them standing high over the landscape, creating a dialogue between them. We look from one to the next to find our direction of travel. So is the land that we travel across as we pass from one destination (cairn) to the next, the 'inbetween' space? The physical spaces between the leaving and arriving - between one destination and the next. Or are the cairns the liminal zones where we linger and look? Both are full of interest. I take photographs and observations on route - the long view

A liminal space can also be defined as the time between the ‘what was’ and the ‘next’; a place of transition, a season of waiting, and not knowing. Where all transformation takes place, if we learn to wait and let it form us.